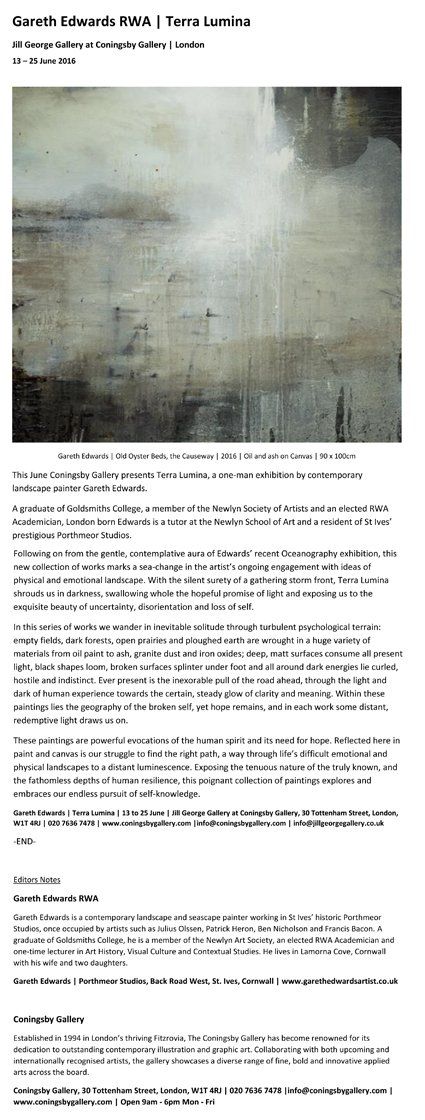

How Creators Create: A Q&A With Contemporary Landscape Painter Gareth Edwards RWA

November 24, 2022

Interview first published at CBAcontent.com

The wood burner was ablaze and fresh paint glistened from canvases on the wall. Gareth leaned in to check a drying drip of colour, seeing if he should flip the canvas around. Satisfied with gravity’s work, he left everything to rest while we settled into our conversation.

Originally from London, Gareth Edwards moved to Cornwall in 2000, in part, to have more space to think, to reimagine and reinterpret the world around him. Today, sitting in his St Ives studio, the elected Royal West of England Academy (RWA) Academician tells us how he intends to keep his eyes wide open for as long as he lives, translating what he sees in nature into art. Not only that, Gareth gives us an inside glimpse into how he became an artist and painter of beautifully emotive landscapes that have the ability to transport you to another place, a past memory, or different mood altogether.

First, we go back to the beginning: childhood.

Celeste: You’ve had and continue to have a phenomenal career as an artist. Have you always considered yourself to be an artist, or was there a defining moment when you decided to embark on this journey of painting?

Gareth: As a child, I’d turn my bedroom into an art gallery once a day and I had these portraits I invented all around it. That was a conscious decision to do at the age of seven. I had a very creative childhood. I didn’t have a father, so I was always painting, always making, I was always in the garage making stuff with saws, hammers, and nails – constantly. I built snail houses and bred snails for racing, and I built a lot of weaponry like crossbows.

I wanted to be an artist at the age of 17 or 18. I was definitely a searcher: it was either going to be poetry or art. One of the few times I remember seeing my father when I was 14 or 15; he took me to a post-impressionist exhibition at The Courtauld. There was Modigliani’s famous painting there called Seated Nude, and you can imagine at my age, being a boy at an all-boys boarding school, and suddenly there were these perfect breasts in the painting so I was pretty obsessed. It was the actual painting that fascinated me, I couldn’t get over these painted nipples and perfect breasts.

I was a footballing, fighting, testosterone-fueled athletic machine. But still, I knew deep down that I was a poet or an artist. I actually bought a postcard of that painting that day at that show with my own pocket money and it became a very treasured thing. I framed it and took it with me wherever I went for 15 years. I did continue my studies in art when I didn’t have to at school and I was told by a teacher that I should be an artist. I did get a grade A for art in O levels/A levels – it’s the only one I ever got.

I knew deep down that I was a poet or an artist.

However, neither of my parents wanted me to do art. They really persuaded me to do business and economics, which I did, and I pursued art in my spare time. Because of that, I couldn’t do a degree in Fine Art at first but I did eventually do a degree in Art History.

At school, there were studios for fine art students and I’d hang out with the artists (art historians were really boring, haha). It was a very feminine time in my life. There were a lot of beautiful women there, so there was a theme. That was graduate school, the London Institute.

In June 1984, after my last exam, I went into the studios and started painting that day and I’ve never stopped painting ever since. I’ve never been trained after O levels; I didn’t have foundation, but I put the brush and the paint in turps. I didn’t have a clue what I was doing, but it just felt like breathing. From that moment, I saw myself as a working artist.

Celeste: You speak very poetically about your art — would you mind expanding upon what you call the “aesthetics of atmosphere” and the “primacy of poetics” in your paintings?

Gareth: When I was a kid, I had a fountain pen (there weren’t many in those days). And I was going to be a writer. I wrote short stories and I painted, I was in between. I think of paintings as poems. Both are about distillation.

I do believe there’s an empirical truth in the world, obviously. Water always boils at the same temperature.You can’t deny this empirical truth. However, I do think there’s an alternative truth that runs alongside. I keep meeting people (in the past and in the present) who want the truth to be one or the other. A lot of artists in the past thought that you had to observe, be a scientist, get a sense of place, record — that’s never ever interested me, it bores the effing pants off me, I can’t bear it!

I was much more interested in the idea of interpretation and imagination. I had a very imaginative childhood. I was free. I was free to access the feminine, the poetic. And I think there is an absolute way that people see the world through poetry, through a poetic truth. Even a shopping list is a cultural thing!

When people see my paintings, they interpret them in a poetic way – their own personal poetry. Empirical truth and poetic truth are parallel lines of truth. I actually witness it when people come to the studio and I build it into my paintings. I don’t want to give people too much information because I don’t want my paintings to be prescribed and descriptive.

I’m very interested in the aesthetics of atmosphere. There’s a whole philosophy around atmosphere; it comes from Henry David Thoreau who was a phenomenologist. He said:

“It’s not what you look at that matters, it’s what you see.”

It’s simple, yet powerful. In between what you are looking at – the stimuli – and what you see, is a gap filled with your interpretation, your history, experience, your culture, your position, your gender, your physiology, your medical health, love, sex – anything. So the image you are looking at has to travel through all those filters until you see. And that gap is the atmosphere.

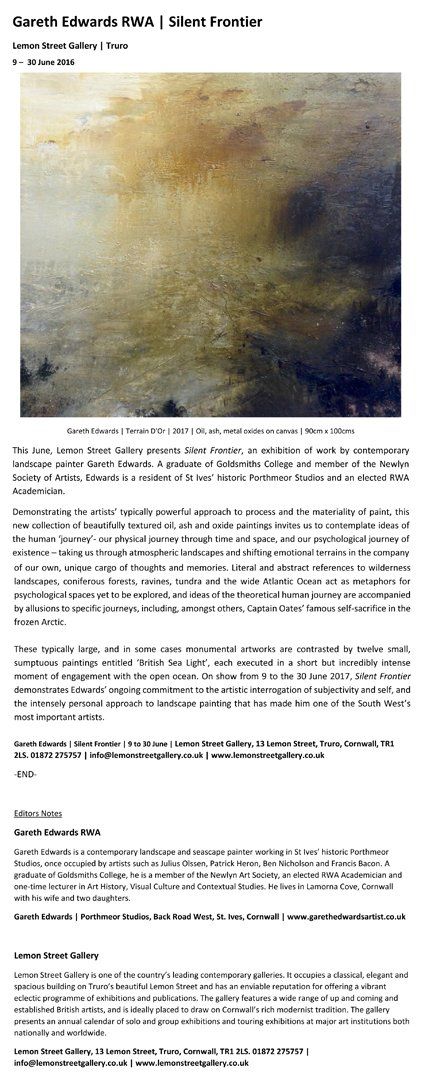

I build my paintings to be atmospheric. For example, you can tell that a certain painting depicts an outside. And then I will build a kind of mood into it. But as to what that mood might be and what it might mean, I leave that entirely up to you. I don’t mind playing games with the idea of interpretation and description, but the key is that they’re all imaginative.

The only certainty is that I’m a human being with a poetic sensibility who’s had his eyes wide open for 60 years.

Celeste: And isn’t atmosphere also kind of what you bring to it as an artist?

Gareth: 10 people will read the same poem and they will all read it differently. When I was doing outdoor workshops, I’d take 10 students with me to paint outside. The conditions and the subject would always be exactly the same for everyone. We would spend an entire morning doing that and then go back to the studio and there were 10 completely different interpretations of the same landscape. And I’d say, welcome to your language, this is your language. Don’t try and be someone else.

None of them told the truth; they all told a truth, a poetic truth. So, there’s always evidence in my head that interpretation and perception in poetry is the key.

I did a series of mountain paintings because I went to the mountains on my own. I slept on one of them in a sleeping bag, and it was frightening, it was dark, but I had this unbelievable experience. I had this feeling of my whole being sinking into the mountain as if I was one with the mountain. It felt like the mountain was a kind of resource, amazing energy, it was like my body and soul were investing into the mountain. The mountain was giving dividends back to me. Nature is like a bank so I called the series Natural Capital.

Celeste: We talked about your tree sculptures before, but I’m curious, have you explored other art forms in the past, or has nature and painting been a constant, consistently capturing your imagination?

Gareth: Yes, certainly. For example, at one point my paintings became like sculptures. It’s easier when you haven’t been trained to be a pretty painter. So I saw material as blocks of building stuff. I felt more like a builder at that time and I was using a lot of materials that weren’t oil paint. And my paintings became more and more like sculptural objects.

But then the painting becomes an object and I didn’t want people to treat my art only as decorative pieces. I know it’s enough for a lot of people – they’re very beautiful; you use lots of pigments and ground-up granite and marble dust, you manipulate it and build it into a painting that then becomes an object. It looks very meaty, sexy, but I realised there was no story. It was just material being beautiful. It wasn’t satisfying to a poet.

I had to include the narrative and storytelling, and at the same time make everything physical. So that was a new thing for me.

A lot of people feel like failures because they stray from what they are taught and they give up.

I did lots of sculptures in plaster, lead, and wood. But my tree exhibition nearly killed me. My fingers were all cut and bleeding. If I made a mistake, I needed another branch, and when it was raining, it was a challenge, so it was a bit bonkers. Then, I went back the next day and they were all covered in black mold so I had to do the whole process all over again. I had to do that three times in six months. There were 12 in total; they did look great but I thought, never again. Sculpture hurts.

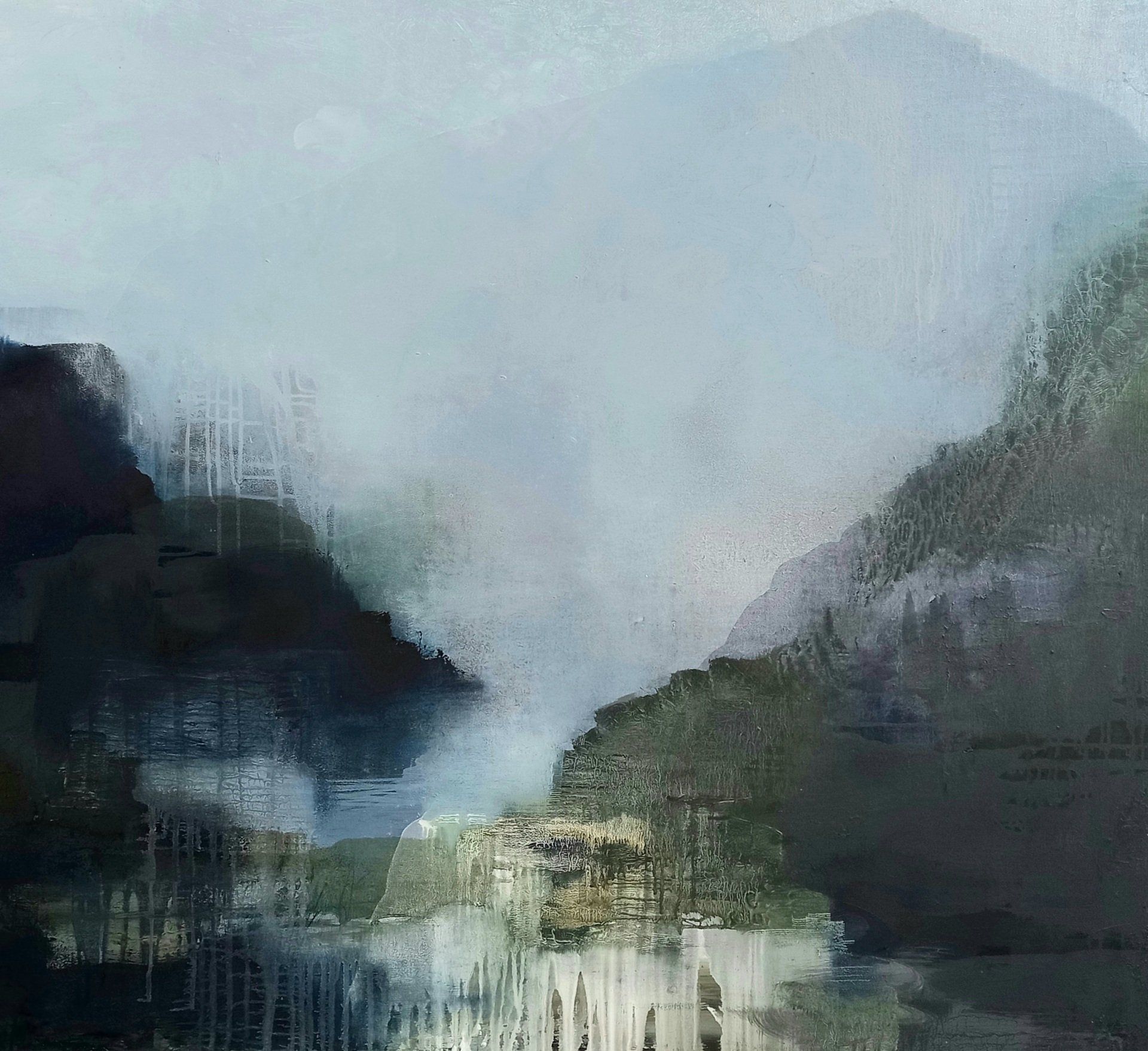

Celeste: Together with your daughter Kate Reeve-Edwards you wrote Painting Abstract Landscapes in which you help people begin their journey into painting landscapes. What makes this book different from other art books, and if there is a key takeaway you would like readers to gain from it, what would it be?

Gareth: Empowerment for the reader to create incredible-looking paintings without recourse to old traditional patriarchal painting skills. You can make incredible work without the old-fashioned brush painting techniques. Also, the importance of poetry and the poetic truth in interpretation. A lot of art education is based on disappointment and I wanted my book to alleviate that.

A lot of people feel like failures because they stray from what they are taught and they give up. This book is built towards success – you almost can’t fail with it. If you get the priming right, you can’t go wrong. Every day I get messages from around the world how this book changed somebody’s life.

It’s about deep processes, pouring, priming, and continents of colour meeting each other and moving around. It is accidental but it’s a managed accident. Because you sometimes turn the painting around and decide it is now a happy painting. It’s all open. You don’t force anything. Paint is fluid, and paint and colour have their own demands, you need to listen to it, see what the painting is trying to tell you.

Celeste: You are a graduate of Goldsmiths College, an elected Royal West of England Academy (RWA) Academician, and a sessional tutor at the Newlyn School of Art. At what point did you decide to become a teacher and why?

Gareth: I started there when the crash happened in 2008. I had been a lecturer of history at university for years beforehand, traveling around the country lecturing MA and BA students about postmodernism.

Until my daughter was born in ’95, I was a London-based artist and my materials were widely different from what I use now. I used to use smoke, raw tongues from the butchers, 6-inch nails, photography, mud, installation, ice – anything I could get my hands on.

Stephen Friedman came into the studio once while I was doing huge smoke paintings. I’d invented this algebra of emotions; I had a glossary and this whole alphabet, so I was making paintings with emotional equations – all made out of smoke. So Stephen came in and told me there was no one doing quite anything quite like it. He was building a gallery in New York and London and told me to give him a call. I still have his card in my wallet, I never called him because I stopped doing those paintings.

What I do is not fashionable. It’s heartfelt and comes from the soul.

It was then that I had my baby. And I felt like a dad, in love with his daughter, and I looked at my art and thought it was all ridiculous. I was a young man with his head up his a**. I built a studio in my garden so that my daughter could play there and all of a sudden I had this painting, the kind of painting that I’m doing now. That was 26 years ago. Having written a book with her now feels like a full circle.

As soon as I began, I felt like I was giving up on art a bit, or rather on the competition. This whole second-tier gallery started wanting my work and it was a kind of success. I did sell out three shows in London, 50-60 paintings per show, hosted private viewings, the queues of people who wanted to see my paintings were extraordinary. It was a very exciting time. But inside I thought, this is not art.

Celeste: Do you still feel like that?

Gareth: Yeah, I think it’s paint poetry. I think art is a construct, published into the mainstream by people like Tate, Newlyn, the Arts Council. It’s fashion’s fad. And what I do is not fashionable. It’s heartfelt and comes from the soul. It’s constant though. I know I’ll be doing this ‘til the day that I die.

Celeste: I think art and what it means to people throughout generations changes. But this physical space, with its history and heritage behind it, has drawn artists here for centuries. I would love to hear a little bit more about how this space (your studio), this town, this place inspires you.

Gareth: It inspires me very much. Together with my partner and our children we wanted to leave London because of the pollution of too much information. London was visually polluted with adverts, pressure, and people with influences. I wanted to be quiet – still – so I could paint.

We came down here (St Ives) initially, because we both liked Patrick Heron’s work. We liked the brilliance of colour and light in his paintings, especially middle to end periods. It was the idea that his paintings could in some way undermine and counteract the dourness of English weather, English life, the hard granite. He reinterpreted this place in terms of light, modern and bright colours. It felt as if we had permission to come down here and interpret it in a modern, reconfigured, reimagined way, rather than being dragged down into an old Hepworthian, worshipful, and classist society.

You can reinvent your own life through painting.

We can breathe bigger, our heads can become full of knowledge, freshening wind, we can become open and liberal – through painting. His paintings summed that up.

Celeste: You have two studios, the one we’re in now (Porthmeor Studios) and one in Penzance. Do you spend half the time there and half here? Or does it depend on your mood?

Gareth: Yeah, depending on mood. At the moment, I’m only doing work on paper there, oil on paper.

Celeste: Did you do oil on paper for your recent Earthland exhibition?

Gareth: I did some, but mostly it was canvases. All the tree paintings, pieces for the British Art Fair, and some of the Earthland show were all done in that studio.

Celeste: Was there a main influence for your Earthland collection? Or did the gallery approach you to make something like this?

Gareth: They rely on me to come up with content. I don’t have any trouble with that at all. I start having thoughts, reveries, daydreams reacting against and for things. I was interested in people’s reactions to the Earthland show so I listened to quite a well-known psychiatrist who came in and bought a couple of big pieces. We had a talk and what she felt about the pieces that she’d bought and about the show, it was very interesting to digest that and to then interpret it and come back to the studio.

People who buy paintings sometimes want to chat. This way I get information about what people are thinking, for instance, of that show. They like the atmosphere, the less prescriptive, descriptive work. And they definitely liked the more optimistic work, and that was a key bit of feedback for me. It made me think of how I’ve been drawn to the darkness for quite a while.

And it’s a trope: an older man, some miserable, old git. I wondered, am I painting myself into a miserable old git? It’s an easy thing to do, the idea of a man my age showing joy and happiness seems somehow suspiciously youthful. After the show, I started thinking…

Can you paint yourself into optimism through colour?

So I thought, Oh, I’ve got to make a happy painting, I wonder if that will make me happier. So it was a project for about two, three weeks after the show: Can you paint yourself happy? Because you can choose. The universe isn’t telling you anything, you’re telling yourself. So I’ve been trying to slowly dig myself out of quite a moody, slightly cynical, bleaker place, and build myself into a more positive place through colour.

I’ve spoken to other artists, friends my age, they all love those despairing paintings but we’re just talking to ourselves. So is that the truth? Because if you talk to yourself, you just repeat. So I bought all these colours and now I’ve got a choice.

A diplomat from Luxemburg told me she liked one of my paintings because it gave her positive dreams. So I decided to ditch the darkness even though it’s so seductive as makeup to be moody and dark and Shelley-like. So I stepped out into pinks and lime greens but I am gonna go gray here and there.

Celeste: You’ve been doing this for a while and you’re a great teacher so my last question is, what advice would you give someone who is just starting out on their own artistic journey, or perhaps someone who would like to be more creative in general?

Gareth: On a personal level, I think it’s really, really important to have a sense of self-determination. It’s a cliché, but the answer isn’t out there. What you think, can be just full of shit. But if you’re following someone else’s lead, or someone else’s tropes and clichés, it might get you somewhere, but you’re never gonna stand out.

Believe that you can reinterpret the world in your own way.

And get some friends when you’re starting out, other people who do similar stuff, so you give comfort to one another. But at some point, you’re going to have to leave those friends and be you. I think that is the hardest part. What is it that you want to say? How are you going to say it? Because if you’ve got nothing to say, you’ll only be left with how you’re going to say things. Those two things have to match up: the materials and your techniques have to match up.

Most of Mozart’s music is jolly so it’s always been a C major. But the two or three pieces he made, like the “Requiem”, they were a bit more unjolly, they’re in D minor. So you have to have the right notes. That’s about the materials as well. I deliberately choose oil paint and techniques that are opposite to what I want to say. So I’m tapping into a tradition and I know exactly what I’m doing. Whereas in the past, I would have never used oil paint, ever, because I wanted to be a contemporary postmodern artist. So I’d use plastic, or a car, or someone’s hair.

Celeste: So it’s okay if your song changes, you just adapt to that change and give yourself permission to change the tune, change the pitch? Maybe if you don’t see something, sometimes you can hear it?

Gareth: Absolutely. Threnody is the Greek word for it, when the means of expression match the expression. Threnody means to lament. The lamenting words are matched by the lamenting sounds.

Celeste: Gareth, thank you so much, for sharing your story and your knowledge with us.

Contact us

Sign up to our newsletter

We will get back to you as soon as possible

Please try again later